This article was authored by Smriti Saini and Shweta Gupta, Research Analysts at The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Most in-person survey activities have become unviable due to COVID-19; however, it is all the more important to continue primary data collection to guide effective policymaking for the communities impacted by the pandemic. The transition to phone-based surveys has almost eliminated the need for physical contact, but it also presents a set of unique challenges that shall form the basis for further learning and developments to improve upon the available mode of phone surveys.

Executive summary

The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) conducted two rounds of surveys for farmers and self-employed women from May to September 2020 to gauge the impact of COVID-19 on their livelihoods. The surveys were conducted via phone, or computer-assisted telephone Interviewing (CATI), as a part of two ongoing initiatives: German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) in India and Nepal, respectively. We were able to reach out to over 70% of respondents in the first round of surveys, facing persistent issues such as multiple call reschedules, incorrect phone numbers, and refusal to participate.

This blog post discusses the methodological and logistical challenges faced in conducting these surveys, insights on how to maneuver these challenges for varying study contexts, and lessons learned. In this post, we also reflect upon the challenges posed by language issues, mobile phone recharges, and explore how to enable enumerators to best deal with these challenges, as well as share preliminary findings on the adverse impacts of COVID-19 and lockdowns on respondents

How phone surveys were conducted

In Nepal, 2,689 maize-growing farmers were interviewed in Dang region, a midwestern district in Terai. Over 70% of these respondents were female farmers. In Gujarat, India, surveys were conducted of 627 women who were members of SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association), a trade union of self-employed women working as farmers, casual laborers, hawkers, and artisans. The objective of the surveys was to determine the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods and income, food security, decision-making, mobility, and intra-household conflict. In addition to this, the surveys in Nepal assessed the impact on the availability of agriculture extension, pest attacks on the maize crop, and migration.

In Nepal, we reached out to the respondents in March at their doorsteps in a household listing exercise for a larger randomized control trial, not anticipating the COVID-19 circumstances. Out of 6,000 farmers surveyed, over 3,700 farmers reported having phone numbers and were included in the present study. In India, a list of 860 women was obtained from SEWA directly and the respondents had been notified by SEWA beforehand to expect a survey call.

Both surveys were performed over the phone using SurveyCTO’s CATI feature. Since strict lockdown conditions were imposed in both study areas at the time of the survey, enumerators were conducting the surveys remotely. The CATI feature enabled enumerators to collect data on the same device from which the phone calls were made. Not all our enumerators had access to computers, hence, our field supervisory team obtained daily updates through manual notes sent via WhatsApp and Viber. We also used KoBoToolbox for systematic updates from the enumerators. Data was monitored for strict adherence to the data collection protocols, and we assessed anomalies in survey duration, outliers, and inconsistent information. In the second round, flagging errors based on the repeat questions from the first round of data collection helped us determine the error rates of enumerators.

Assessing technical knowledge of enumerators

The case management element of the SurveyCTO CATI starter kit enables enumerators to conduct a respondent-wise survey with easy tracking of respondents for multiple survey rounds. However, in cases where data collection happens virtually with no physical supervision, it requires considerable training of the enumerators to ensure complete understanding of the CATI features and the relevant technical aspects. Depending on the comfort and caliber of the survey team, research teams may have to conduct multiple pilots to ensure that enumerators obtain an enhanced understanding of each feature. We paired enumerators to practice with each other over the phone and made it mandatory for them to try out each possible call scenario on their mobile devices such as a dropped call, rescheduling, and a family member picking up the phone. We then examined the practice data to assess understanding and followed up with a discussion with enumerators. Depending upon the feedback received, additional training sessions may be required for some enumerators.

Challenges in ensuring high response rates

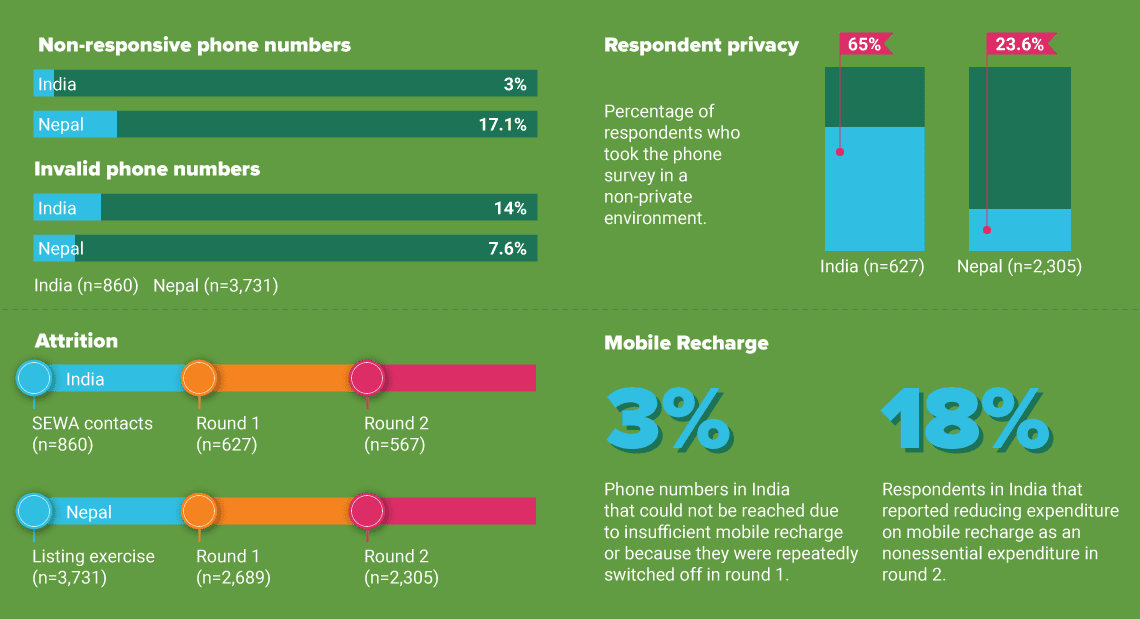

Despite obtaining phone numbers that were either self-verified in Nepal, or verified by the mediating organization in India, both surveys suffered from considerable attrition rates in the first round. Only 72-73% of respondents could be reached to administer the survey in both studies. A significant fraction of phone numbers–7% in Nepal and 14% in India–were either non-functional or belonged to the wrong household. Apart from that, nearly 3% of respondents in Nepal and 6% in India refused to participate in the survey, despite the promise of participation incentives like phone recharges and food mini-kits. Call attempts were made to reach the respondents over a stretch of 5 to 6 days, and around 17% of respondents never answered the call in Nepal. In India, 4% of phone numbers were lost to this issue.

Most of these problems were persistent even in the second round of the survey. However, the response rate improved in the second round at 90% and 85% in India and Nepal, respectively. In the second round we were down to 2,305 respondents in Nepal from 2,689 respondents in the first round, and 567 respondents from 627 in India, respectively.

Before beginning the actual survey, it is recommended to verify the phone numbers to estimate the extent of non-working numbers. If possible, substitute phone numbers should be obtained with the help of the enumerators, respondents’ friends or neighbors, and through partners on the ground.

Building trust with respondents

A major challenge in conducting phone surveys is ensuring that trust and rapport between the enumerator and the respondent is built, given that the enumerator is reduced to a faceless agent. The prior physical listing exercise in Nepal enabled familiarity of the respondents with the enumerators and the data collection exercise. While physical listing will not be feasible for some time, collaborating with an organization on the ground–in this case SEWA in India–can help in obtaining working phone numbers and build familiarity with respondents; however, researchers need to be wary of selection bias. When surveying female respondents, it may be useful to work with female enumerators to ensure the comfort of the respondent.

Considering respondent privacy for sensitive information

Our surveys included a few sensitive questions on topics such as household conflict. These questions are susceptible to response biases such as social desirability bias, and researchers should confirm the respondent’s privacy before asking such questions, especially for female respondents.

Over 65% of respondents in India were found to be taking the survey in a non-private environment and hence, they were not asked the sensitive questions. In Nepal, respondents were given a knowledge test, and hence, it became necessary to know whether they were receiving information inputs from another family member. We initiated our surveys with non-sensitive questions first and moved the sensitive ones towards the end of the survey. Doing so helps the enumerator to build trust with the respondent. Once enough rapport is established, we could ask sensitive questions and expect more genuine responses.

It is important to note that the issue of respondent privacy can be dependent on the study context. Compared to India, only 24% of respondents in Nepal were in a non-private environment during the survey, with no significant difference in male and female respondents. Since we were operating in sensitive contexts, we did not ask or direct our respondents to move to a private environment as this may have not been perceived well by other family members.

Assessing cost of mobile phone services as an access barrier

A potential barrier to phone surveys is the non-reachability of phone numbers due to insufficient mobile talk time balance on the respondent’s phone. Around 3% of the phone numbers in India could not be reached in the first round because there was either not enough mobile recharge in these phones or the phones were repeatedly found switched off. In the second round of the survey in India, about 18% of the sample self-reported that they had reduced the expenditure on mobile phone recharge because they considered it to be a non-essential expenditure, compared to other more pressing needs like food and water. In Nepal, around 41% of respondents reported that they had reduced expenditure on household items, which included phone recharge, to deal with the lockdown induced income loss. Other respondents had shared the phone numbers of friends or neighbors since they themselves did not own a mobile phone, a case documented in both countries. Incentives such as phone recharge may help address this problem for studies with multiple survey rounds.

Determining the best time to call

In India, around 65% of the surveys were conducted in the second half of the day from 12 pm to 6 pm, since most women found it suitable to talk during that time. But in Nepal, around 62% of the surveys were conducted in the first half of the day from 8 am to 2 pm. We had to adapt the call timings to the cropping pattern in the region. Many paddy-growers were surveyed at night as they had requested. It is imperative to stay attuned to the conditions in the field to vary call timings, which can be done via data monitoring and regular check-ins with the survey team.

Prevalence of language issues and hearing disabilities

Regional dialects that are hard for enumerators to understand can pose serious challenges for phone surveys. In many cases, respondents reported hearing and other language issues thereby asking their family members to complete the survey on their behalf. Since this survey was designed for the specific respondent, we instructed enumerators to let the family members answer the questions which were not respondent-specific or sensitive. Data loss and increased survey duration should be expected in such cases as enumerators have to reiterate many questions. Patchy network and other connectivity issues can also cause errors in recording responses; hence, it is recommended to repeat the same questions in multiple-round surveys to record the extent of such errors. It may be helpful to rope in local and regional enumerators who have some understanding of regional languages and dialects.

As phone surveys become the new normal, it is exigent that these issues are documented, studied, and addressed. It becomes necessary to adapt data collection protocols to unexpected challenges, as highlighted here, especially in times of uncertainty as imposed by the pandemic.

Preliminary survey findings

In addition to the above learnings, the preliminary analysis of the surveys revealed significant adverse impacts of COVID-19 and lockdowns on rural livelihoods. In Nepal, farmers reported that they could not access the farm produce market and agriculture inputs promptly due to the lockdown. Earnings from work and remittances declined for over 70% of households after the lockdown. Well after six months of the initial lockdown, 40% of households were still using their savings to cope with the crisis, and over 30% had reduced expenditure on food items. In India, on the other hand, nearly 88% of the women surveyed reported a decline in household income due to COVID-19 lockdowns, of which 76% reduced consumption and 56% used their savings to supplement the loss of income. Most farmers also reported issues due to poor access to up-to-date information and uncertainty during the lockdown.

Learn more

To learn more about the work that BMZ and CSISA have been doing on the impact of COVID-19, please reach out to Ms. Smriti Saini, Research Analyst, IFPRI, at s.saini@cgiar.org and Ms. Shweta Gupta, Research Analyst, IFPRI at shweta.gupta@cgiar.org.